“But Patrick’s love lives on”

“Fentanyl killed my son” is printed on the front of a t-shirt worn by Stephanie Defelicibus.

“But Patrick’s love still lives on,” is printed on the back. It’s the “most bold thing I did,” said Defelicibus, who lost her son, Patrick John Kilbane, to a fatal drug overdose on March 28, 2020.

One year after he died, Patrick’s godmother made a pin with his face on it for Defelicibus and other family members to wear. The pin often makes people curious, and Defelicibus uses it as an opportunity to shine a light on Patrick’s life, and raise awareness about drug overdose.

“If people ask, I tell them, ‘that’s my son who passed away,’” she said.

The shirt also attracts plenty of attention whenever Defelicibus wears it in public. Most people take a moment to connect and relate to her tragic loss.

“They’re not critical,” Defelicibus said. “They always say, ‘Well, I lost one myself, or my niece or daughter or son is struggling with addiction.’”

Despite the negative stigma that often accompanies addiction, Defelicibus feels comfortable telling people “as much as they need to know” about Patrick. Whether she’s in grief counseling or out in public, the mother of four doesn’t shy away from questions about why her son lost his life.

The front of Stephanie Defelicibus’ shirt says “Fentanyl killed my son.” The back of the shirt says “But Patrick’s love lives on.” (Photo provided)

“Fentanyl killed my son”

Defelicibus remembers having breakfast when the call came from the medical examiner. A neighbor found Patrick lying on the kitchen floor of his apartment at roughly 6:00 a.m. on March 28.

Police initially suspected that a “white substance” was the cause of Patrick’s overdose, according to Defelicibus. However, she believes it was “100% fentanyl.” Toxicology reports did confirm the presence of fentanyl in Patrick’s system.

“I used to say it was an overdose,” Defelicibus said. “Some of us parents say he was murdered. It was fentanyl poisoning. Yeah, he made a bad choice that night. He tried something that was all fentanyl.”

According to Lori Cross, director of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services in Ohio, fentanyl played a part in 81% of the state’s drug overdose deaths. Fentanyl-related deaths continue to dominate the headlines as the powerful synthetic opioid (50 to 100 stronger than morphine) spreads through drug supplies across the United States. Patrick was one of more than 5,000 Ohioans to die of a drug overdose in 2020. During that time, COVID-19 affected businesses worldwide, including the drug market.

With borders closed, drugs were harder to traffic into the United States. However, fentanyl was still available and easy to move, considering it’s trafficked in international mail and packages.

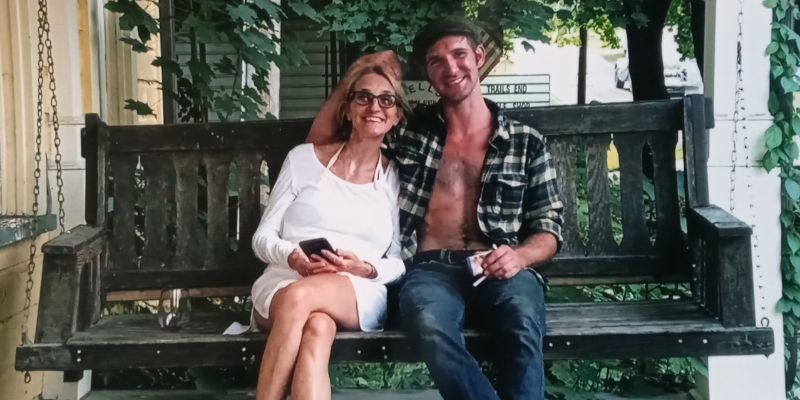

Patrick Kilbane’s godmother made Stephanie Defelicibus and other family members pins with his face on it to remember his life. (photo provided by Stephanie Defelicibus)

“Sometimes we all just need a little reminder”

Patrick was born on March 21, 1992. He’s described as someone who showed his love and appreciation for family and friends (including his two dogs) with regular phone calls. He often reached out to the people in his life, checking in with them to see how they were. It’s a model that Defelicibus and her family try to follow in their everyday lives. A model that says, in Patrick’s own words, “sometimes we all just need a little reminder.”

He died roughly one week after his 28th birthday. Instead of gathering to recognize the day he died, Defelicibus said the family celebrates Patrick’s birthday at some of his favorite places, where they can remember his impact.

“People can share their story of Patrick and keep their memories alive in a positive way. Not just how he died,” Defelicibus said.

“He was overthinking things”

After two unsuccessful attempts to stay sober, including inpatient rehab at nearby Glenbeigh Hospital, Patrick seemed to have finally found a path to recovery.

“There was a point where he decided to accept the help,” Defelicibus said.

Patrick graduated from drug court and went on to Matt Talbot for Men, an addiction treatment center part of the Catholic Charities Services in Parma. For almost four years, from 2017-2020, his recovery seemed secure. Patrick had a job, a girlfriend and an apartment.

“He was doing well,” Defelicibus said.

However, at some point, Patrick’s struggles with mental health caught up to him. He stopped doing activities to sustain his recovery.

“He didn’t keep up with the AA groups,” Defelicbus said. “I think mental illness and drug use are interconnected.”

While Patrick wasn’t officially diagnosed with any mental health disorders, Defelicibus believes there was a connection between paranoia and his substance use. Many people experiencing substance use disorder (SUD) also deal with mental disorders.

“He wasn’t in a good place, ” Defelicibus said. “I think he was overthinking things.”

Patrick’s overdose happened during Ohio’s “Safe at Home” order, aimed at slowing the spread of COVID-19. Uncertainty about the virus caused many Ohioans to “panic buy” everything from hand sanitizer to toilet paper. Defelicibus noticed Patrick was worried about supplies leading up to the state-mandated shutdown. He told her she needed to buy liquor and cigarettes because those would be good things to barter with.

Like many people during the COVID lockdown, Patrick seemed agitated and scared. His paranoia also caused him to believe the police were following him, according to Defelicibus. She was worried he’d started drinking again.

“He was drinking alcohol the night he died,” said Defelicibus, who found alcohol in Patrick’s apartment after he died. “He was probably drinking for awhile.”

Patrick John Kilbane was described as someone who showed his love and appreciation for family and friends (including his two dogs) with regular phone calls. (photo provided by Stephanie Defelicibus)

Mother Traces Son’s Tracks

Patrick was by himself when his neighbor found him. However, because his wallet was missing, Defelicibus suspected he wasn’t alone the night he overdosed.

“When I was able to get into his apartment, his wallet was nowhere to be found,” Defelicibus said.

She suspected the wallet was stolen because Patrick always put his wallet and keys inside his hat.

“That’s why I pushed for camera surveillance and found out they identified this young woman that was with him,” Defelicibus said.

With the help of detectives, Defelicibus was able to retrace her son’s steps to an ATM. Patrick and the unknown woman were spotted withdrawing money Defelicibus believes was used to purchase the fatal drugs.

“I think he took out $50,” she said. “There was only $10 in his pocket when I got his belongings.”

Police tracked down the woman after she used Patrick’s bank card and money at local stores and restaurants.

“I don’t know if she was using with him,” said Defelicibus, who thinks the woman was with Patrick when he overdosed. “I don’t know if she was the one that supplied it or helped him contact somebody to get the stuff. But he died and she didn’t. She left, didn’t call the police and took his wallet.”

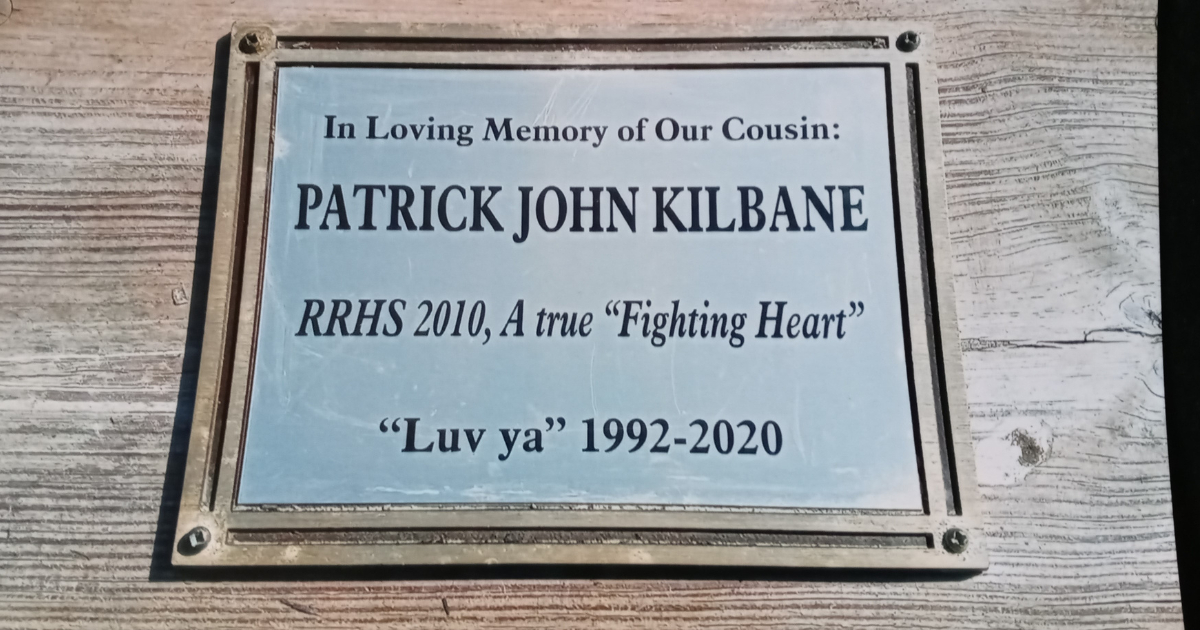

Patrick Kilbane’s cousins planted a tree in his memory, where this memorial plaque now sits. (Photo provided by Stephanie Defelicibus)

A Group to Grieve Overdose Deaths

To cope with her son’s passing, Defelicibus joined a local support group called Grief Recovery After a Substance Passing (GRASP). A childhood friend who lost her son introduced Defelicibus to the group, which meets near Cleveland.

“As soon as she found out on Facebook that Patrick died, she contacted me,” Defelicibus said.

Many parents talk about the stigma attached to addiction. When they lose children, some say the stigma follows the parents in their grieving process. Some parents lose loved ones to cancer or suicide, but the ones who lose a child to substance abuse find it hard to make a connection in traditional grief groups.

Many parents deal with the notion that something they did lead their child to use drugs. Society often makes us feel like someone who died from an overdose was a bad person. GRASP gives parents like Defelicibus a community to grieve with. It’s helped her deal with her own feelings and the judgment of others.

“Those were the moms I was able to identify with – moms that have gone through losing their children,” she said.

GRASP meetings are open to adults over the age of 18 who’ve been in the grief process for at least a year. Active addiction is not discussed, and meetings are held in person only.

Click here to find a meeting in your area.

Avoid Overdoses With Addiction Treatment

We share overdose stories to bring awareness to the public health crisis that is drug and alcohol addiction. Recovery is possible with the proper care and treatment options, like residential treatment or intensive outpatient programs.

At Landmark Recovery, we provide a safe place for patients to detox and learn the skills needed to cope with their addiction triggers and temptations.

If you think you or a loved one has a problem with drugs or alcohol, don’t hesitate – get help today. For more information, call 888-448-0302 to speak to a member of the admissions team, or visit our locations page to find a treatment center near you. We’re available 24/7.

If you live in or near Ohio, we have treatment centers in Euclid and Willard.

Choose Recovery Over Addiction

We're here 24/7 to help you get the care you need to live life on your terms, without drugs or alcohol. Talk to our recovery specialists today and learn about our integrated treatment programs.